|

I GREW up in Australia. It's a long a way away from, well, everywhere. You know the drill. In Australia we have ridiculously cool wildlife: kangaroos that hop around, koalas that look cute but are some nasty a** pieces and then all the super cute, innocuous animals like wombats, Tasmanian devils, sharks, snakes...wait! Wildlife are some of the things that make Australia extraordinary. But, despite its distance from nearly everywhere else in the world, I don't want to be the one to tell you, but, a lot of Australia is actually ordinary. Growing up in the seventies and eighties in Australia mostly meant growing up in a house with a backyard, a garage, and possibly a shed. These domestic spaces did much to reinforce certain types of activity. Children in the yard, women in the home, and men in the garage or the shed (if they were lucky). Although this played out in a low rise, suburban fashion, amidst Eucalyptus trees and against the sight and sounds of Australian fauna and flora, the reality is that these were domestic hangups that happened everywhere around the world. The man cave, as I like to call it, was like a shrine of sorts. A place where men in particular got fundamental work done. Cars may have occasionally been fixed there. Card games played. Tools neatly stored with love and respect. A Pirelli calendar to be stared at while contemplating the greater questions of life? Possibly.  Photo: Ansis Starks, source: Armpit catalogue Photo: Ansis Starks, source: Armpit catalogue These traditional male spaces were a global phenomenon before the majority of my generation and the one that followed realised we could free up all our time by just paying someone else to do the dirty work. They were serious and significant places for men the world over, and places that women on the whole dismissed as spaces where men simply wasted their time, tinkering away. Artists Katrina Neiburga and Andris Eglitis have re-imagined these mythical spaces for the kind of daily spaceships that they are/were with Armpit. It's an exhaustive mix of lo-fi and hi-fi technology. Think digital screens mixed in with roughly set, home built wooden spaces, in tribute to the ubiquitous if, quickly disappearing man-shed and that home made aesthetic that just ruled the domestic world back then (ie. back before we started paying everyone to actually renovate and do the work). Those places that transported men into another world. Fertile grounds for the imagination, particularly in the old Soviet states where technical, hand skills were highly prized, and where isolation from much of the world's existing technology meant that invention was a solidly encouraged goal or objective to have. I really loved this exhibit. I found that it was really creative and playful and that it said so much on so many different levels. Let's consider that like Georgia, Latvia is a reasonably small country that exists on the edge of Russia, and that it too is not immune from the geopolitics that Russia has been involved in of late.

Going back in time in the Pavilion to the Soviet era spaceships and a time in which autonomy had a time and place (in the domestic space) can partly be interpreted as a retreat from the politics that happen near the border today. It's also an enthralling study on the changing face of gender, but gender is such a dirty word here in Italy right now that I'm going to leave you to draw your own conclusions. What did you think? Did you love it as much as I did? Let me know in the comments. One of my six picks at Arsenale. Loved it!

0 Comments

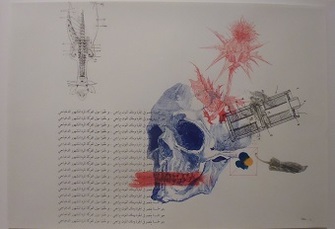

THIS is a partner post to my guide to a day at Giardini at the Venice Biennale. You’ll find all the practical information about getting to the Biennale and its layout on that post. Just a note to remember. Forty eight hours in Venice will give you ample time to visit the bulk of the ticketed sites, and probably enough time to visit nearby exhibits like Macau and Hong Kong. Seventy two hours will give you the ideal amount of time to soak in Venice and navigate around its maze of canals so that you get a taste of the best of the collateral events too. But be warned. Venues are closed on Mondays, so if you’re thinking of making a long weekend out of your trip, be ready to hit the pavements on Friday morning. To get the most out of Arsenale you’ll need a full day. On Fridays and Saturdays the site is currently open until 8pm…worth noting and taking a packed lunch if you’re prepared to be a real trooper! This year there’s a lot to see at Arsenale, particularly in the Corderie and Artiglierie areas which function as collective exhibitions and that host over 100 different artists this year. This in addition to a couple of dozen international pavilions that are scattered around the old ship yards. There’s so much different work on show, particularly in the Corderie and Artiglierie that it would be impossible to cover in a single blog post. So what I’m going to do is focus on the six things I think you should not miss here and let you explore this maze at your own pace. In addition, I’ll give you the tips for what I think are the six best national pavilions scattered around Arsenale and then a couple of little diversions to keep it challenging.  Monica Bonvicini, Latent Combustion Monica Bonvicini, Latent Combustion After you make your way through the obligatory (and always enjoyable) Bruce Nauman light pieces, you’ll eventually begin to run into the work of the late Terry Adkins. His sculptural pieces which often blend brittle and softer more tactile materials are exhibited in a way that allows us to enjoy his abstract pieces and to respectfully lament his passing. Nearby Terry Adkins’ work is a piece by Italian artist Monica Bonvicini (Room #2). A former winner of the Golden Lion (1999), Bonvicini, in addition to being a presence on the international biennale scene, has also exhibited in major spaces since taking home the prize. Latent Combustion (2015) is a jarring, conceptual installation piece. Like roses being hung and dried, Bonvicini suspends her bouquets of black, rubber lacquered chainsaws from the ceiling. They dare you to walk in and amongst them, repelling you with their muted violence and the pungent smell that the industrial materials off set. Nidhal Chamekh studied at the Fine Arts school of Tunis and lives and works in Paris. In light of recent events that have taken place in his native Tunisia, Chamekh’s series De quoi rêvent les martyrs 2 (EN: what do martyrs dream of 2) is sadly poignant. Artists rarely commit to large scale works without doing preparatory drawings (or digital designs beforehand these days). Martyrs on the other hand focus on the end and their end goals.  Nidhal Chamekh, De quoi revent les martyrs 2 Nidhal Chamekh, De quoi revent les martyrs 2 Preparatory drawings often are a starting point, a beginning point, and as such offer the chance to step back into the beginning, rather than focus on the end. In these beautifully drawn works, Chamekh seeks to transgress back to the original, starting point, to address the disturbed dream states of people who are willing to create acts of atrocity. These technically well drawn, though ominous images are carefully designed. Chamekh sparingly introduces colour into certain works and avoids it elsewhere, suggesting that these fitful dream states and obsessions are devoid of the vibrancy of life, even in their embryonic phases. You might at this point step out for a breath of fresh air or some natural light to reset those pupils of yours. If you head out of one of the doors on the left handside as your making your way through the Corderie, you’ll make a pleasant discovery of Ibrahim Mahama’s rather phenomenal Out Of Bounds. It’s an installation of epic proportions, made of sacks that cover and transform the entire passage way that runs parallel to the Corderie. The young Ghanian artist uses these fibre sacks like a patchwork, achieving something that only large scale public works (usually done by much more experienced artists) are capable of. Here, the installation speaks of the inequality that is rife not only around world, but through the art world too. Covering the Corderie with a network of this fragile and sturdy object speaks volumes not only of Ghana’s economy but of the inequality that is even on show at an international art exhibition. Incredibly powerful!

Gerald Machona - Ndiri Afronaut Gerald Machona - Ndiri Afronaut I DON'T know about you, but I know that when I go to certain international events, there are certain countries I root for. For me, South Africa is one of these countries. I think of South Africa as Australia's distant cousin in many senses. When I'm with South African friends or meet South Africans, there is a sense of kinship I think I feel with them. I'm not suggesting that Australia and South Africa are identical, and nor that they have dealt with their own historical mistakes and deplorable pasts in the same way. But internationally, there are some cultures that just seem to gel better with others, in part because though they may be thousands of miles apart, they share more than just an essence. There's a kinship that grows when you share similar demons that in a large part you inherited from your parents (even if you made them your own) . Culturally, South Africa today is still processing its past on the international stage, in part because it still has wounds that need tending to, and in part because the world seems not to have learned sufficiently from South Africa's history. I try to keep an eye on what is happening down in South Africa. When artists travel Europe's way I make a bee line for them...for example, each year I look forward to seeing Dada Masilo's dance creations when they come to Rome. I look forward to them as eagerly as I do visiting the South African pavilion each Biennale...it's my own way of rooting for a country. This year, for What Remains Is Tomorrow, over a dozen artists have been drawn together to explore "imaginary truths''' and ''ideal narratives'. The idea behind the show is to mix the contemporary in with moments of the past, in a bid to address the themes of power, freedom and civil liberty in South Africa. And as always, South African artists are not afraid to really probe. Anything that contributes to a healthy, open debate. South African culture is a layered and complicated beast, and as such, What Remains Is Tomorrow, seeks to explore this complexity through a range of media. Despite the complexity of a group setting such as this, I will say that much of the exhibit seems like it has been really honed in, aided by the strong monochromatic theme that takes precedence and keeps things clean rather than cluttered despite the range of mediums. Piquing my interest at the exhibit, were three artists who work across a range of media themselves. Gerald Machona, whose Ndiri Afronaut (I am an Afronaut) comprised of a sculptural piece (made of, amongst other things, decomissioned Zimbabwean dollars) and an accompanying video which was both moving and entertaining (and visually stunning). Machona's work here refers to recent events which suggest that the ethnic violence (towards Zimbabweans who make up a sizeable part of the community in South Africa following the waves of migrants who fled the failed economic state) is flaring again. A lesson that perhaps South Africa and the rest world have not yet mastered. Robin Rhode's Blackness Blooms, which alludes to Don Mattera's poem of the same name was also wonderful. An eight part C-type series in which an Afro comb teases and nurtures a head of follicles until it blossoms into a wonderful, complete and bold hairdo, rich in symbolism. Engaging and a lovely mix of the traditional with a dash of street thrown in. One of my other highlights from the show (the amount of video in the show warrants at least a half hour in the pavilion and more if you want to do everything justice) was Moha Modsiakeng's Inzilo video. Do you remember those old gelatin photos with their rich silvery layers and beautiful blacks and whites? Well Modsiakeng achieves that finish with digital precision in his video Inzilo. Taken from the word representing mourning/fasting, Inzilo features Moha going through an intimate, private ritual, a rite of passage, but although its a very focused and inward journey, it is a private act for the public's benefit.

There's a lot to get through in South Africa's reasonably compact pavilion, but although its too layered to cover in sufficient detail here, you'll find it's one of the best pavilions of the year at Arsenale this year. In part because (inter)national ideas and concerns are largely given individual, humanist forms, even within the group setting. One of my top six at Arsenale. Was it one of yours? Leave me a comment to let me know your thoughts. Heri Dono is arguably Indonesia's most famous artist on the world scene. Indonesia, Australia's northern neighbour, is not widely cited in art circles beyond the Asia Pacific. Instead, read anything about Indonesia and you're likely to be reminded that it's the country with the world's largest Muslim population. Though this may be true, it is a sign of Indonesia's more recent (re)incarnation. It's also the backbone of a world view that is as much a sign of our times as it is of our tendency to simplify the complexity of history and cultures. The Indonesian archipelago has had a long history thanks to its placement within the South East Asian economic routes and was the subject of ongoing fascination of European colonial powers from the 1500s. Indeed, the Portuguese, British and Dutch all had a vested interest in Indonesia, which culminated in the Dutch establishing the Dutch East Indies, a colony (formed mostly of modern day Indonesia) which endured until the end of the second world war. Why the history lesson? Because it's important to understand the context of modern Indonesia through what it endured before declaring independence. This is a complex and fascinating nation that is more than the home to Bali or SE Asia's most important Islamic centre. This is a place that can attest to the effects of colonialism for one thing. A place whose indigenous tribes were studied by Western anthropologists, a nation whose pluralist religious systems (and their associated artistic expressions) contributed much to the West's obsession with ethnography that was rampant throughout Asia. A country whose complexity can't be accounted for by simple titles like most populous Muslim nation. We're talking about an archipelago made up of up to 17,000 islands, at least half of which are inhabited. How do you define that? Heri Dono begins from this view point, and for Voyage/Trokomod goes about turning the traditional ethnographic and political perceptions inside out. But it's not just the external perceptions that get folded in on themselves. Heri Dono is also interested in laying bare the inner divisions that occur in his native country. This is a nation that is riddled not only with divergent cultures and customs, but one that is marked by its own history of occupation and the presence of radicals and separatists (much like many modern nations). So how to go about turning the internal and external on their ear? By entering into the mentality that lies within. And the vehicle is a war horse, suggesting that there's a lot going on within 'Indonesia'. By situating a Trojan horse within the walls of the pavilion, Heri Dodo is representing the beast within and challenging us to explore the nation within and not just beyond its international boundaries. This is no Classical Western war machine. It's menacing like a world power but also incorporates its own soft power ethic by tapping into the Indonesian identity. Think a cross breed of Trojan horse and Komodo dragon (hence the Trokomod label). This ingenious and menacing entity has a hard exterior but is soft on the inside: incorporating traditional local textures like rattan and batik to temper its ferocity and the religious symbols that kept ethnographers so fascinated. They are protected by that iron shell which has its own agenda. Hovering around the beast are the familiar motifs of Heri Dodo's angels who are free to roam, unconstrained.

But what about those canons you see on the Trokomod? Well they function more like periscopes, and here is where the genius exists. It is here that East truly meets West. Peep inside and the ethnographic traditions get flipped: inside you'll spy curios from the Western world. It's a role reversal that suggests that there is more than one world vision on offer should we be prepared to entertain it, and more than one way to place Indonesia in the global context. And thus, Heri Dodo and Indonesia achieve a mix of humour, reflection and the blurring of intercultural boundaries that many of other countries at this year's Biennale fail to. We've all got a lot on our plates, and we're not all in the mood to play, but thankfully, someone has a sense of humour at the Biennale this year. One of my top six picks for Arsenale this year. Was it one of yours?  The Republic of Kosovo, one of the world's most recently defined nations. A place that fitfully came into being after years of ethnic conflict and military action. A state that is now immersed in diplomatic negotiations in an attempt to be unanimously recognised by the international community. Artist Flaka Haliti (b.1982) is representing the European nation with the youngest median age with Speculating On The Blue. So how does Haliti make sense of Kosovo's past, present and future? And what it does it mean on a more global level? Haliti's installation is site specific. Like a tiny, land locked nation it is wedged into a tiny space, abutted by countries whose inhabitants have higher average ages and whose sovereignty were recognised much earlier, but often under similar circumstances. Like a territory that is pockmarked and scarred by the darker sides of politics and violence, her tiny space is reduced to being furnished only with what remains. In this case it's sand, metal and light. Suggestions and remnants of a military zone, of conflict, with terrain that is hard to plow through and a low horizon line that breaks through the remnants of walls and barriers that had been constructed to separate and redefine a setting. Acts that gave new identity to the generation that erected them, but that the artist deconstructs. These are broken remnants of walls, and walls that have gaps in them are useless, meaningless. They can be navigated around, walked through, and can not even hope to successfully contain what sits within them, no matter the effort spent in creating them. A remarkable highlight at Arsenale this year, and one of my top six there. An island nation of just 12,000 people. The smallest country represented at the Venice Biennale this year. A place where the highest peak is just a couple of dozen metres above sea level. A country that is doing its utmost to use any and every international forum to draw attention and seek help to counteract the very real prospect of it vanishing under water in the face of global warming and rising sea levels.

This is Tuvalu's second outing at the Biennale. Their first outing was memorable. This time around, Taiwanese artist, Vincent J. Huang (yes, he's back again) is more subtle with Crossing The Tide, but the urgency of the issue at stake remains. While last time around Huang required user participation, this time around he's trying a softer approach. The installation beautifully calling to mind the blue waters of the Pacific, and leaving visitors to contemplate the environment. The adoption of the Daoist principles of Zhuangzi's ancient text that noted that there was no separation between man and nature. But an odd decision has been made by the curatorial board. While it's admirable that the pavilion has adopted a paper free policy, encouraging visitors instead to visit the website, the lack of any immediate didactic information in the room, that could otherwise steer the mostly European audiences towards the goals and aims of this largely unknown country, is a lost opportunity. Perhaps the curators can find some way of incorporating some textual information before the peak summer run. That said, despite the urgency of the environmental situation, the deceptively tranquil environment offers a refuge from neighbouring pavilions. Geysers occasionally erupt with a low whirring gush, blowing steam from the walls, misting up the environment and playing with the preconceived ideas of island paradises. This is one of Venice's most effective presentations this year. If anyone is an authority on the environmental challenges posed by global warming, then it's Tuvalu. In many ways one could say that they have more authority on the issue than a landlocked nation like Switzerland who have approached the theme in a similar way this year. That said, it's nice to know that this crucial aspect of our future is being addressed by more than one artist and national board, particularly under the light of All The World's Futures. Definitely one of my six picks at Arsenale. If we can always count on Korea to bring their A game to the Biennale, then the one other certainty is that you can rely on Serbia to make a grand political statement. And not in a way that aims to whitewash the political reality.

The Ottoman Empire. Tibet. Yugoslavia. The United Arab Republic. Nation states that no longer exist but whose echoes still persist. And in the setting of the Venice Biennale, the soft power Olympiad, where the nations that still exist on the map duke it out, what do these spectral nations tell us about the fleeting nature of art and sovreignity? Ivan Grubano's United Dead Nations seems like a simple and straightforward idea for that cavernous space. Then you get to thinking, how many years did it take him to scour the globe to find original flags from the dead countries he eulogizes on the walls? The flags that are reduced to dhobi wallah rags, dipped in paint and beaten against the floor, their blood and grit left for us to walk all over before we consider which pavilion to visit next. Flags that from a distance look like collateral victims on war grounds. But our own desires will soon enough take us elsewhere...we're free to continue roaming the international playground of art, free as such to skip from country to country. But only if we can liberate ourselves from those who no longer have a nationhood to ascribe to. Those who for a variety of reasons exist now only like faint memories or in old atlases. Collectables in an age when the symbolism of art and soft power representation can be stripped at any moment of their significance, and be sent the way of obsolete and now powerless nations from history. This year at Giardini was a mixed bag for some of the regular Biennale hard hitters. I walked away with all kinds of disappointment and audible grunts after visiting the US, French and Austrian pavilions. Ditto for the Netherlands and Denmark. Thank god that there are certain nations on whom you can rely to always bring their A game. And the refreshing thing is that they are not the usual suspects. No, in fact, the countries that I think really put a lot of thought and effort into their Biennale showcases are generally punching above their weight: yes, I'm talking about you Hungary and Serbia. They totally know how to show up a super power! But if we are going to talk about consistency and staying 'on-brand', then we don't need to look any further than the Korean pavilion. They nail it. Every single time! This year, with The Ways of Folding Space & Flying, Moon Kyungwon & Jeon Joonho embark on a kind of digital archaeological quest back in time, raising questions about the relevancy of the current notion we have of art and asking what place will art hold in the future?

[South] Korea is one of the countries that always thoughtfully considers the themes of a biennale and carries them out to the letter. They have a way of mixing in their trademark technology in a way that almost embarrasses their Giardini neighbours, but just enough East Asian philosophy in the mix to consistently elevate the works beyond being simply technical. The title of this year's project for All The World's Futures comes from the Korean words chukjibeop and bihaengsul. Based on Taoist practice, chukjibeop means hypothetically contracting physical distances. Bihaengsul, on the other hand, refers to the supernatural ability to levitate, and travel across time and space. As such the themes, which in a way also feed into meditation practice, suggest the desire we have as people to overcome our barriers, and that can only be achieved through an eventual leap in our imaginations (and abilities). The work which is all digital, engrossed visitors, and kept them in the pavilion longer than the works in others did. People would have happily camped out or picnicked in the pavilion had they had the chance. While they sat watching the huge screens, the protagonist in the film ran like a hamster in a wheel that was like a temporal mobius strip, generating power and giving her the ability to go back in time. The motif of renaissance era figures working away as artisans was jarring and audible: the clanging of metals signalling the arrival of, the futuristic type...but wait...just who was that person from the past? The studio quality of the work was undeniable. By also being visible on the pavilion's exterior, something few other nations (aside from Norway perhaps) bothered with, the Koreans tapped into the year's obsession with borders and the idea of inclusion and exclusion. A crowd favourite for sure. Impressive and slick, and worth putting a half hour or so aside for if you have the patience and want to enjoy it to full effect.  You recognise this face. You know who he was. Why? Because of his undeniable talent and prolific work ethic? Yes. Partly. But also because Salvador Dali was one of the first artists to use modern media to transcend the art scene, and become a persona with a distinct public image. He did this by navigating his way across the international media, creating not just a name for himself, but an enduring, symbolic presence. The blurring of the line between public and private. It was a blue print that super artists like Warhol would later adopt. One of the things I hated about studying art history was the preparedness with which one had to accept the dogma of art historians. There are certain belief systems in the field of art that have very clear rules to them, and not adhering to them, or supporting established theories is frowned upon. This I found ridiculous of course, as history is made by people but written by historians, and therefore subject to subjectivity and prevailing fashions and beliefs. Why the rant? Because in visiting the Spanish pavilion at the Biennale, you need to be prepared to read between the lines. Like art history, society, and in this case, European society, is dictated by a set of norms: of codes that are written and unwritten. But they can't account for everything. We as individuals can't simply be defined by definitions that are imposed upon us. We bend and break and especially for those of us on the margins of society, are capable of seeing things that the masses cannot. This is the premise for Los Sujetos (The Subjects), an ambitious collective show curated by Marti Manen. It's a show that breaks the Spanish pavilion's recent run of solo and pair shows to bring together artists from different corners of the Iberian peninsula. And where does Salvador Dali fit into this? He's the muse and ringmaster for a modern take on his influence: not so much as a Spanish art great, but more as a master of the media and public image. After all, with figures like Dali and Warhol, what they said (offstage) and did was often just as important as what they produced (on-stage). What's happening in the Spanish pavilion this year seems to be about the arbitrary boundaries that we push against suggesting that society's one size fits all approach is no longer working. In Helena Cabello and Ana Carceller's contribution The State of the Question, Dali's one time lover/cohort, Amanda Lear, is referenced, both in the showcases and a video piece where her song I'm A Mystery is performed by a group whose identities are fluid and in flux. Transgender? Gay? Different race? It doesn't matter...none of these tags can define them. Cabello and Carceller have long incorporated questions of gender into their work. But what place does this have in Venice you might ask? Well, Italy is gripped by a new wave of obsession with gender and civil unions. Just this past weekend, almost a million conservatives, convened by the Catholic church, marched through Rome in protest under the guise of "Family Day". It seems existence beyond the traditional family unit remains a no go for the right wing parts of this society. The message? Conform to the norms or remain invisible and keep you mouths shut The reality is that minorities don't need to be acknowledged. They just need to slot in to the bigger system which otherwise alienates them. But if you look carefully enough, there are instances where they make unhealthy partners. Look at the press for example. Beyond the mainstream, weeklies/monthlies like comics compete with crossword rags to remain mainstays in Italian culture. I don't know anyone here who hasn't read Dylan dog or done the puzzles in La Settimana Enigmistica. Francesc Ruiz explores the mirroring systems of the alt/mainstream press and the crack between them. Each of these media types has its own outlet and commercial system in place, and if you've visited any mainstream newsstand (Italian: edicola) in Italy, you'll have seen how much written content competes for shelf space in them. In Edicola Mundo, Ruiz creates two newsstands, each brimming with content. In the mainstream stand, Ruiz recreates blank publications and displays them in repeated patterns, our eye attracted to things that look familiar but say nothing to us. Like codes that have no meaning. Of the little text available is one which alludes to Berlusconi's infamous virility and bunga bunga parties. In the other stand, a different kind of sexuality is being peddled. That for gay men, but behind the cover of a concealing tarp, which gives its customers anonymity but further separates them from the masses. Inside, more repetition, a trademark of Ruiz''s work, but an explosion of color. More codes and hidden meanings, and references to Italy's erotic comics, but rather than unmet desire, here sexuality is amped up and ready to blow. These cultural fault lines are everywhere and have entered into our unconscious thinking.

With Dali and Warhol, we never got the satisfaction of knowing when the show started and where the show ended. We've come into a phase of our being where our obsession with celebrity has led to us creating celebrities of our own, letting their reality shows into our lounge rooms. We watch as participants run through semi scripted activities for the camera and endure the endless replays of seemingly pivotal moments. More than glittering success, pop culture loves a spectacular fall from grace. We waited with baited breath for it to happen with Michael Jackson, were resigned to it eventually happening to Whitney, but still bear the traces of our shock when Britney went postal. The menacing nature of on stage and off stage worlds seems to pique the interest of Pepo Salazar, an artist and writer who works across a variety of mediums who contributes two seemingly intertwined installation pieces to Los Sujetos. At face value it's cheeky and irreverent. But look closer and you'll see that Salazar is actually motivated by the chaos that is brewing between [on] stage and off stage worlds. The ripple effect caused by the sheer anarchy of the breakdown of a popular figure. In this case think glass cases of cheetos, mirrors, shaved heads and wigs strewn about, while in the partner piece abandoned microphones are mechanically dragged around in circles, creating disc shapes on an industrial floor. And Dali? He's taken his bow but is still at the centre of it all. His own interviews with the press playing away on the video screens, in the centre of the pavilion. The ringmaster, in historical footage of him courting celebrity, but at the same time, risking the creation of a ripple in the grander order of things by blurring the lines...and allowing us to reconsider his influence beyond the usual art historical prism. You know we're in a sorry state when humour is the victim at the Biennale.

This year, very few countries or artists have put forward something that will bring a smile to your face, and you will have to seek them out. If you've a perverted sense of humour like I do, then Sarah Lucas' work (British Pavilion), in spite of its socio-political themes will make you think and laugh, as will Spain's take on what we've been reduced to in contemporary culture (more soon on that one). Even the awkward clutter of Canada's BGL Collective will feel like temporary respite. But beyond that, the Biennale hasn't been as political of late as it is this year. European nations in particular seem to have a lot on their conscience this year, meaning many of them aren't in the mood to play. There's a lot of soul searching going on, and even before the events of 2011, Japan was already in a contemplative and questioning mood. This year's Japanese offering, Chiharu Shiota's The Key In The Hand, is positively dripping in retrospection, but, it's shaping up to be one of the year's biggest hits with visitors. Why? Because it achieves its aims with the kind of wistful romanticism that you find on the canals of Venice but that is otherwise completely lacking at the Biennale. Shiota presents a large scale and painstakingly detailed installation alongside some endearing videos in the outdoor pilotis. In the installation, two wooden boats are placed like catchments for a deluge of keys hanging from an intricate maze of red yarn that is suspended from the ceiling. Each string bears a key, a memory that can be contained and locked away for safe keeping in times of uncertainty. Outside, the video monitors present children who recall their own memories to the camera: they playfully and resolutely share their memories of event before and after their own births, a touching and poignant means of pointing to the questionable accuracy of memory. But in our current political climate, the installation as a whole also works on another level beyond the protective warmth of memory. Globally we find ourselves at a time when boats have a renewed political and intercultural significance, and where Shiota's keys could just as easily be the keys to unlocking and forging new realities and memories. This dual sense of hope has not been lost on visitors such as myself, who are already enamored of the work's intricate but straightforward, formal beauty. Whatever your interpretation, The Key In The Hand, is a welcome respite from the storm of discontent which seems to be brewing all around it, and for me at least, the standout at Giardini for emotional punch. |

Dave

|

|

|

Dave Di Vito is a writer, teacher and former curator.He's also the author of the Vinyl Tiger series and Replace The Sky.

For information about upcoming writing projects subscribe to the mailing list. Dave hates SPAM so he won't trouble you with any of his own. He promises. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed