|

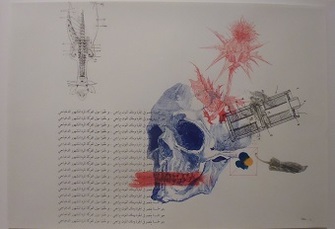

THIS is a partner post to my guide to a day at Giardini at the Venice Biennale. You’ll find all the practical information about getting to the Biennale and its layout on that post. Just a note to remember. Forty eight hours in Venice will give you ample time to visit the bulk of the ticketed sites, and probably enough time to visit nearby exhibits like Macau and Hong Kong. Seventy two hours will give you the ideal amount of time to soak in Venice and navigate around its maze of canals so that you get a taste of the best of the collateral events too. But be warned. Venues are closed on Mondays, so if you’re thinking of making a long weekend out of your trip, be ready to hit the pavements on Friday morning. To get the most out of Arsenale you’ll need a full day. On Fridays and Saturdays the site is currently open until 8pm…worth noting and taking a packed lunch if you’re prepared to be a real trooper! This year there’s a lot to see at Arsenale, particularly in the Corderie and Artiglierie areas which function as collective exhibitions and that host over 100 different artists this year. This in addition to a couple of dozen international pavilions that are scattered around the old ship yards. There’s so much different work on show, particularly in the Corderie and Artiglierie that it would be impossible to cover in a single blog post. So what I’m going to do is focus on the six things I think you should not miss here and let you explore this maze at your own pace. In addition, I’ll give you the tips for what I think are the six best national pavilions scattered around Arsenale and then a couple of little diversions to keep it challenging.  Monica Bonvicini, Latent Combustion Monica Bonvicini, Latent Combustion After you make your way through the obligatory (and always enjoyable) Bruce Nauman light pieces, you’ll eventually begin to run into the work of the late Terry Adkins. His sculptural pieces which often blend brittle and softer more tactile materials are exhibited in a way that allows us to enjoy his abstract pieces and to respectfully lament his passing. Nearby Terry Adkins’ work is a piece by Italian artist Monica Bonvicini (Room #2). A former winner of the Golden Lion (1999), Bonvicini, in addition to being a presence on the international biennale scene, has also exhibited in major spaces since taking home the prize. Latent Combustion (2015) is a jarring, conceptual installation piece. Like roses being hung and dried, Bonvicini suspends her bouquets of black, rubber lacquered chainsaws from the ceiling. They dare you to walk in and amongst them, repelling you with their muted violence and the pungent smell that the industrial materials off set. Nidhal Chamekh studied at the Fine Arts school of Tunis and lives and works in Paris. In light of recent events that have taken place in his native Tunisia, Chamekh’s series De quoi rêvent les martyrs 2 (EN: what do martyrs dream of 2) is sadly poignant. Artists rarely commit to large scale works without doing preparatory drawings (or digital designs beforehand these days). Martyrs on the other hand focus on the end and their end goals.  Nidhal Chamekh, De quoi revent les martyrs 2 Nidhal Chamekh, De quoi revent les martyrs 2 Preparatory drawings often are a starting point, a beginning point, and as such offer the chance to step back into the beginning, rather than focus on the end. In these beautifully drawn works, Chamekh seeks to transgress back to the original, starting point, to address the disturbed dream states of people who are willing to create acts of atrocity. These technically well drawn, though ominous images are carefully designed. Chamekh sparingly introduces colour into certain works and avoids it elsewhere, suggesting that these fitful dream states and obsessions are devoid of the vibrancy of life, even in their embryonic phases. You might at this point step out for a breath of fresh air or some natural light to reset those pupils of yours. If you head out of one of the doors on the left handside as your making your way through the Corderie, you’ll make a pleasant discovery of Ibrahim Mahama’s rather phenomenal Out Of Bounds. It’s an installation of epic proportions, made of sacks that cover and transform the entire passage way that runs parallel to the Corderie. The young Ghanian artist uses these fibre sacks like a patchwork, achieving something that only large scale public works (usually done by much more experienced artists) are capable of. Here, the installation speaks of the inequality that is rife not only around world, but through the art world too. Covering the Corderie with a network of this fragile and sturdy object speaks volumes not only of Ghana’s economy but of the inequality that is even on show at an international art exhibition. Incredibly powerful!

0 Comments

Heri Dono is arguably Indonesia's most famous artist on the world scene. Indonesia, Australia's northern neighbour, is not widely cited in art circles beyond the Asia Pacific. Instead, read anything about Indonesia and you're likely to be reminded that it's the country with the world's largest Muslim population. Though this may be true, it is a sign of Indonesia's more recent (re)incarnation. It's also the backbone of a world view that is as much a sign of our times as it is of our tendency to simplify the complexity of history and cultures. The Indonesian archipelago has had a long history thanks to its placement within the South East Asian economic routes and was the subject of ongoing fascination of European colonial powers from the 1500s. Indeed, the Portuguese, British and Dutch all had a vested interest in Indonesia, which culminated in the Dutch establishing the Dutch East Indies, a colony (formed mostly of modern day Indonesia) which endured until the end of the second world war. Why the history lesson? Because it's important to understand the context of modern Indonesia through what it endured before declaring independence. This is a complex and fascinating nation that is more than the home to Bali or SE Asia's most important Islamic centre. This is a place that can attest to the effects of colonialism for one thing. A place whose indigenous tribes were studied by Western anthropologists, a nation whose pluralist religious systems (and their associated artistic expressions) contributed much to the West's obsession with ethnography that was rampant throughout Asia. A country whose complexity can't be accounted for by simple titles like most populous Muslim nation. We're talking about an archipelago made up of up to 17,000 islands, at least half of which are inhabited. How do you define that? Heri Dono begins from this view point, and for Voyage/Trokomod goes about turning the traditional ethnographic and political perceptions inside out. But it's not just the external perceptions that get folded in on themselves. Heri Dono is also interested in laying bare the inner divisions that occur in his native country. This is a nation that is riddled not only with divergent cultures and customs, but one that is marked by its own history of occupation and the presence of radicals and separatists (much like many modern nations). So how to go about turning the internal and external on their ear? By entering into the mentality that lies within. And the vehicle is a war horse, suggesting that there's a lot going on within 'Indonesia'. By situating a Trojan horse within the walls of the pavilion, Heri Dodo is representing the beast within and challenging us to explore the nation within and not just beyond its international boundaries. This is no Classical Western war machine. It's menacing like a world power but also incorporates its own soft power ethic by tapping into the Indonesian identity. Think a cross breed of Trojan horse and Komodo dragon (hence the Trokomod label). This ingenious and menacing entity has a hard exterior but is soft on the inside: incorporating traditional local textures like rattan and batik to temper its ferocity and the religious symbols that kept ethnographers so fascinated. They are protected by that iron shell which has its own agenda. Hovering around the beast are the familiar motifs of Heri Dodo's angels who are free to roam, unconstrained.

But what about those canons you see on the Trokomod? Well they function more like periscopes, and here is where the genius exists. It is here that East truly meets West. Peep inside and the ethnographic traditions get flipped: inside you'll spy curios from the Western world. It's a role reversal that suggests that there is more than one world vision on offer should we be prepared to entertain it, and more than one way to place Indonesia in the global context. And thus, Heri Dodo and Indonesia achieve a mix of humour, reflection and the blurring of intercultural boundaries that many of other countries at this year's Biennale fail to. We've all got a lot on our plates, and we're not all in the mood to play, but thankfully, someone has a sense of humour at the Biennale this year. One of my top six picks for Arsenale this year. Was it one of yours? |

Dave

|

|

|

Dave Di Vito is a writer, teacher and former curator.He's also the author of the Vinyl Tiger series and Replace The Sky.

For information about upcoming writing projects subscribe to the mailing list. Dave hates SPAM so he won't trouble you with any of his own. He promises. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed