|

In a year where the themes of the Biennale draw from Leonora Carrington's surrealist children's book Milk of Dreams, the appearance of characters from fairy tales in the exhibition spaces should be of no concern to us. But in Denmark, something has gone wrong. We are left to bear witness to what's left of a Nordic fairy tale. There's an element of decay, perhaps also of crops or an environment that has suffered some kind of tragic fate. In any case, the centaurs won't be living on. In fact, they've met their ends in dramatic circumstances, the male centaur strung up for all to see, the female centaur abandoned in the midst of giving birth. In We Walked The Earth, artist Uffe Isolotto renders us archaeologists, leaving us very little in the way of clues. We see deterioration all around us, with the remnants of the natural world dried up and decaying around us as we survey the scene.  The hyper-realism of Isolotto's figures and their sheer scale make their gothic fate all the more disturbing to us. In their own, unique way, they symbolise both the natural and the human worlds rolled into one, but neither proves to be victorious. We Walked the Earth they declared, silently, And Now We Are Water. The magical realism of this exhibition, while completely different to much that was on offer at the Biennale this year, fit very well with the Surrealist themes of the main exhibition. At a push, I can imagine how the subtheme of humans and the earth connects here. In any case, it was lovely to see Denmark step away from video works and present something that was both sad and whimsical. PRACTICALS You'll need a ticket to Giardini to see this exhibition. Tip: There is an accompanying booklet called And Now We Are Water, but you'll probably want to take it home and then light up a spliff before reading it. Artist; Uffe Isolotto Curator; Jacob Lillemose

0 Comments

This year, The Australia Council, the bigwigs who get the final say on who represents Australia at the Biennale, made the commendable decision of opting for a pretty audacious, experimental installation.

In selecting artist Marco Fusinato to represent Australia this year, they essentially allow the Australian pavilion to deliver the Biennale's one, true rock star moment of the year. Of all the shows that I saw this year, DESASTRES felt the edgiest. It was, at least, the closest any national pavilion got to offering up a truly experimental experience. There's a handful of nations whose approach to the Biennale often leaves me cold.

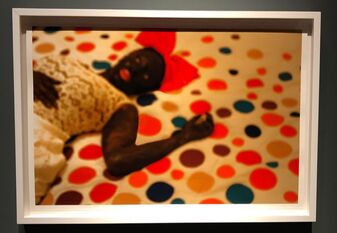

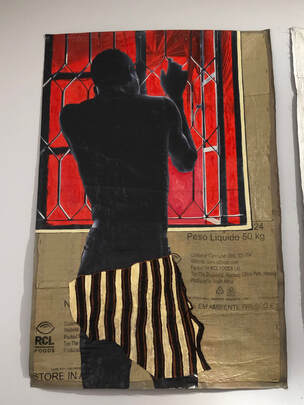

Often, rather than offering their artists the chance to reach out, their pavilions feel like they would be better suited to an expo rather than an art fair. While they're busy using their spaces to pitch just how wonderful their countries are - at the expense of giving a local artist a chance to pursue an idea - the exercise often winds up as a failed attempt at winning over hearts and minds. I don't need to be dazzled by the technology a country has at its disposal. I won't be swayed by the private collection of some oil magnate that's being put on show. I'd rather your organising committee commissioned a set of childrens' drawings at that point. So imagine my utter surprise this year, as I walked out of the Saudi Arabian pavilion, completely blown away. In preparation for the Biennale, every country makes strategic decisions. They have to decide who is going to represent them and why. They have to focus on whether a truly contemporary artist should produce a work specific to the year's Biennale, or whether they can opt to draw from a collection, using a modernish artist to present an aspect of their country's society or artworld. Do they put forward a solo show, a collective or use the platform to show the work of multiple artists? The Biennale is the world's oldest and longest running art fair, but it is a tale of haves and don't have yets. For every established country that has decades' of experience exhibiting, established networks and the tools they need to put on a show, there are also "emerging art" nations who are new to, or still in the early days of their association. Add a pandemic to the complexity already provided by transport, logistics and costs and you can get a feeling for how countries have to make their decisions. This year, as with most years, I enjoyed trips into established pavilions (like South Africa) as much a I did to visits to pavilions run by first timers Uganda and second timers Ghana. The themes, styles and approaches in those three pavilions varied widely, but in each of the exhibits there was one artist that really stood out for me.  SOUTH AFRICA In the South African pavilion, of the three artists whose work was on show, it was Lebohang Kganye's B(l)ack to Fairy Tales, with all its whimsy, nostalgia and sheer bonkersness that completely enthralled me. Essentially, Kganye casts herself as Snow Black, working her way into a series of self portraits. But we're not talking Hans Christian Andersen here; she's moving in and out of the world of fairy tales, but the settings are always in African townships. There's so much going on in the images; the lack of sharpness in the image reminds us that we're under the spell of hazy memories and the settings ask us to think about the realities that people in South Africa have to face every day. (Arsenale)  UGANDA For their first ever Biennale, Uganda elected to go with two established artists; Acaye Kerunen and Collin Sekajugo for the Radiance: They dream In Time exhibition. The pavilion, a collateral event at the Biennale, meaning it is located in the city of Venice rather than at the Giardini and Arsenale grounds, offered a mix of sculpture, installations and paintings but it was the sometimes painting, sometimes collage work of Collin Sekajugo that I loved the most. Frankly, I was trepidacious about even setting foot into the Ugandan pavilion, given the country's horrific record when it comes to LGBT citizens, but I am really glad I did. Uganda's own organising committee, in its notes on the exhibit, points to how Uganda's art scene is still fledgling. But the quality of the work on show here, especially in Sekajugo's Call Centre Girls makes it worth tracking down in Venice if you can get google maps to cooperate long enough.  GHANA also elected for a multiple artist approach for this, its second Biennale. This year, three artists were selected by the director of the country's institute of arts and head of musuems and cultural heritage- Nana Oforiatta Ayim - to represent Ghana in Black Star, this year's presentation at the Biennale. Of the three artists showing, it was the work of Na Chainkua Reindorf which appealed to me most. Whilst Chainkua Reindorf created a site specific installation for the show, it was her paintings that appealed to me most. The paintings, which sometimes include textiles and traditional fabrics, recast women into roles that have always been reserved for men in Ghana's myths and narratives. Her images, which are at times playful and thought provoking, are incredibly graphic in nature, yet with the inclusion of the fabrics, they seem to interweave traditional elements into the works. PRACTICALS For the Ghana and South Africa exhibitions, you'll need a ticket to Arsenale. For the Uganda exhibition, you'll need a good map and sturdy walking shoes. If there are two pavilions at the Biennale that almost always leave me frustrated, its the Russian and Swiss pavilions.

There, I said it. This year, due to the invasion of Ukraine, Russia has essentially been "expelled" from the Biennale. I'll be honest. I'm not sure how I feel about the world's embargo on Russia when it comes to art, culture and artists. To say it’s been a tough couple of years for everyone would be an understatement. Despite the ongoing problems we’re facing with the combined challenges of a pandemic, war in Ukraine and the pressures we’re experiencing with supply chains and inflation in almost every corner of the globe, there are some lights on the horizon, if we actively search them out.

This year, after the pandemic scuttled the scheduled 2021 edition of the Venice Biennale, it’s finally back after three years and some false starts. I have to say, having lived out the pandemic in Italy, a country which was amongst the first and hardest hit, I had really been looking forward to returning to the Biennale. If you’ve visited this blog in the past, you may have noted that the Biennale is my favourite event in Italy, and one of the few times where I feel my masters in art curatorship gets a workout. It’s that time of year when I put my curator hat back on and try and give you the benefit of my experience (and very subjective opinion) to make sure you get the most out of your visit to the Venice Biennale. The Venice Art Biennale is one of few fixed events in my calendar that I make sure I never miss. Every time I go to Venice it takes my breath away. I don’t know whether that’s because of the extortionate prices they charge for practically anything, because the city’s just so fucking beautiful or because these days I only go there for the Biennale and I find myself lost in my thoughts when I’m there. Factor in the bonus of some artporn and a few spritzes and the Art Biennale usually makes for a perfect weekend away for an art nerd like myself. For me the anticipation often starts a few months’ earlier than the actual visit. If I haven’t already begun sleuthing of my own accord I usually start getting excited about it all when I receive a couple of texts to translate for promotional purposes or for the gallery wall panels.

This year’s May You Live In Interesting Times- the fifth consecutive Biennale I’ve attended- had all the same build up of Biennales past but the actual reality of the visit marked something of a change for me. Usually after each visit I really struggle to whittle down the national pavilions to a concise best of the best. I have to go through my notes and reflect a lot in order to get my head around what I saw and what spoke the most to the curator and the artist in me. (You may or may not know that I was a curator and gallerist once upon a time). I inevitably end up feeling like I’m short changing a few artists because so many had something exceptional to offer. Worse still, I normally spend so much time being enthralled at a national level that the central, combined exhibitions feel like an obligation that I have to get through, carefully managing what little time I have left to search out the gems and filter out the distractions and all the noise. This year was almost a complete reversal for me. I found myself struggling to enjoy many of the national presentations and instead more enthralled by what was on show in the collective exhibits which under Ralph Rugoff’s curation felt unified, cohesive and engaging where in the past they were often a rambling, time consuming mess. I won’t go into Giardini and Arsenale just yet- they’ll get separate posts as per the tradition of this blog. But I will say this: if you’re planning on heading to the Biennale this year you’ll do well to manage your level of expectation, especially if you’ve visited Biennales in the past. This year there’s very little that’s playful or fun and humour is in very short supply. This year is a serious Biennale and worse still, very few artists who had a national showcase to play with managed to really hit the mark. So you’ll have to be patient and pace yourself until the highlights present themselves (and sometimes re-present themselves) and make the long, expensive vaporetto ride seem worthwhile. And of course get a leg up with my tips and suggestions. Me and my crew spent the train ride over to Arsenale chewing over some story doing the rounds on social media. I don't remember what it was but it was the reason we ended up having a pretty heavy morning chat that day.

The crux was how in Italy too many people are quick to reduce the ultimate role of women down to mother/potential mother. There's no alternative on offer and worse still, no acceptable argument against it. We noted that the obsession with woman as creator is well, lazy and limited and especially overused in the arts. I know, we could've spoken about the croissants or the scenery but some days you see something on social media and it takes you out on a tangent. Not all that different to what's on offer at the Biennale- where lots of artists are following their own tangents spurred on by themes that will be familiar if you're on social media or if you read the press. Arsenale has less national pavilions than Giardini, so there are a few honourable mentions in this round up of what I think are the ten (+1) pavilions you should focus on. Reality is the huge group show (90+ artists which will get a separate post) is going to gobble up most of your time so you'll want to make the best of whatever time is left over. I'm starting somewhere unexpected- New Zealand to be precise. Lisa Reihana (Emissaries) gets a tick for the best use of space at Arsenale. She's made a kind of panoramic video that mimicks the old scenic wallpapers popular in Europe once upon a time and fills the long narrow space that NZ has been allocated this year. The video is interesting if a little heavy handed for the Biennale. Reihana has basically brought the conversation gripping a lot of former colonial countries to life: the one in which we are starting to articulate imperialism by bringing the darkness of the acts of colonial founding fathers to light. The scale of the work is impressive and it's not too dissimilar in theme to the work of Claudia Fontes (The Horse Problem, Argentina). Fontes is using the symbols of Argentina's founding myth to address angst and frustration. Colonialism, paternalism and the overarching state narrative are not so much the white elephant in the room but a white horse who is chomping at the bit and ready to explode from frustration with the state (as represented by the national pavilion). My friends think I've taken the easy option in choosing Fontes as one of the highlights: her work here is bold, pretty and striking but I also think it's one of the more intelligent uses of space and a pretty powerful subervsive statement about the spectacle of nationalism that makes the Venice Biennale both fun and ridiculous. Spare a thought then for Tunisia. It's not had an easy time of late politically or socially. I'm giving it a special mention because despite political obstacles, they (like the NSK collective) have managed to bring a political protest to the Biennale. The Absence of Paths is an installation: a booth where attendants will issue anyone a passport (a feesa). Its value is questionable and its blue ink (required for your fingerprint) frustratingly difficult to remove afterwards. Its a simple bureaucratic act- a passport or a visa issued instantly - which offers comment on the refugee crisis and it happens so quickly that you wind up thinking (and trying to wipe off the stain of bureaucracy) only afterwards. There are few things that I love more in Italy than the Venice Biennale.

I feel an immense sense of privilege that I have been able to visit it four times since I've been here. Each year I do my best to write up my thoughts in the hopes that my impressions can help other visitors make choices about what to focus on- or give people who have no plans on visiting a down to earth curator's view on things. There are 29 national pavilions in addition to the group show at the Venice Pavilion here at Giardini and this post is dedicated to my favourites. A separate post about Arsenale- the other main complex of pavilions will follow. About a third of the national pavilions at Giardini were offering up what I thought were brilliant or thought provoking work. The ten that I've selected here are more or less in line with the selections of my Biennale crew- this is the fourth Biennale we've visited together and although we usually bicker like sad old toffs on the train ride home this year we pretty much had consensus with our choices. There were a lot of disappointing exhibits on offer at Giardini- especially from Great Britain (too art school), Spain and Holland (too much video and not engaging at that) which are usually my favourites- leaving me with the idea that this year it's Arsenale that is really worth the extra time and effort. But a visit to Giardini will still blow you away if you spend more of your time at the following national pavilions (in no particular order): 1. Germany 2. Japan 3. South Korea 4. Hungary 5. Russia 6. Australia 7. Brazil 8. Israel 9. Greece 10. Czech Republic More detailed comments about these pavilions and the artists after the jump.  wmagazine wmagazine THERE'S something about Tom Ford. I don't know if it is just the devilish good looks, the straight out sauciness or the hint of Botox, but whatever it is, me likey. Apparently the jury at this year's Venice Film Festival half what agrees. They awarded him the Silver Lion for Nocturnal Animals. Well, half of the award for Best Director anyway, as he had to share it with Amat Escalante who was also awarded for Untamed. Those jurists were clearly feeling a bit frisky, and wanted to give in to their wild sides based on the titles of those films. But seriously, Tom Ford is an icon and a reminder that you too can be recognised and rewarded for your brilliance, even if your past involves getting down and dirty with inanimate objects! |

Dave

|

|

|

Dave Di Vito is a writer, teacher and former curator.He's also the author of the Vinyl Tiger series and Replace The Sky.

For information about upcoming writing projects subscribe to the mailing list. Dave hates SPAM so he won't trouble you with any of his own. He promises. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed