|

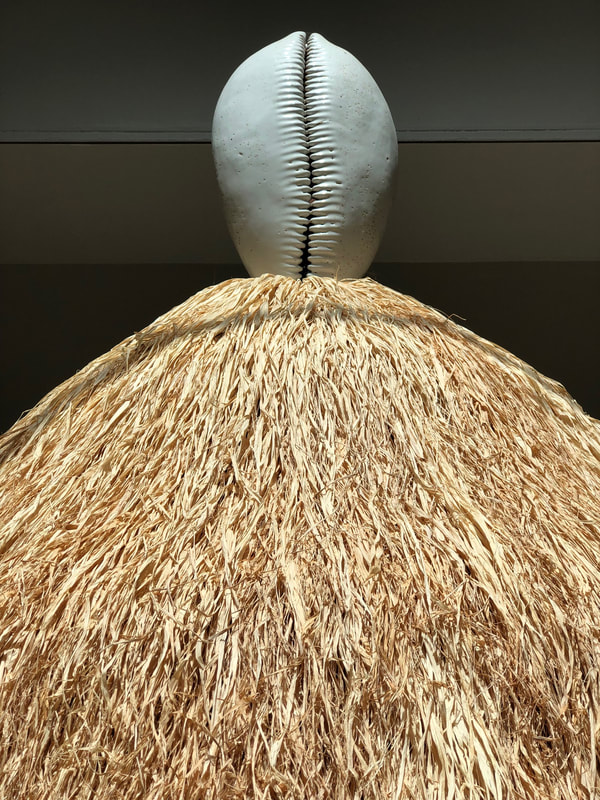

Alongside Gian Maria Tosatti, if by sheer scale alone, there's another artist that has put their stamp all over the 2022 Venice Biennale, it's Simone Leigh.

Art, as we know, is often called upon to represent the world around us. Sometimes, it represents the world as the artist sees it, but other times, it requires the artist to make a leap and represent something that they would like to see.

0 Comments

In a year where the themes of the Biennale draw from Leonora Carrington's surrealist children's book Milk of Dreams, the appearance of characters from fairy tales in the exhibition spaces should be of no concern to us. But in Denmark, something has gone wrong. We are left to bear witness to what's left of a Nordic fairy tale. There's an element of decay, perhaps also of crops or an environment that has suffered some kind of tragic fate. In any case, the centaurs won't be living on. In fact, they've met their ends in dramatic circumstances, the male centaur strung up for all to see, the female centaur abandoned in the midst of giving birth. In We Walked The Earth, artist Uffe Isolotto renders us archaeologists, leaving us very little in the way of clues. We see deterioration all around us, with the remnants of the natural world dried up and decaying around us as we survey the scene.  The hyper-realism of Isolotto's figures and their sheer scale make their gothic fate all the more disturbing to us. In their own, unique way, they symbolise both the natural and the human worlds rolled into one, but neither proves to be victorious. We Walked the Earth they declared, silently, And Now We Are Water. The magical realism of this exhibition, while completely different to much that was on offer at the Biennale this year, fit very well with the Surrealist themes of the main exhibition. At a push, I can imagine how the subtheme of humans and the earth connects here. In any case, it was lovely to see Denmark step away from video works and present something that was both sad and whimsical. PRACTICALS You'll need a ticket to Giardini to see this exhibition. Tip: There is an accompanying booklet called And Now We Are Water, but you'll probably want to take it home and then light up a spliff before reading it. Artist; Uffe Isolotto Curator; Jacob Lillemose This year, The Australia Council, the bigwigs who get the final say on who represents Australia at the Biennale, made the commendable decision of opting for a pretty audacious, experimental installation.

In selecting artist Marco Fusinato to represent Australia this year, they essentially allow the Australian pavilion to deliver the Biennale's one, true rock star moment of the year. Of all the shows that I saw this year, DESASTRES felt the edgiest. It was, at least, the closest any national pavilion got to offering up a truly experimental experience. As the host nation, Italy's run at the Biennale in recent years has been hit and miss, if you ask me.

For the most part, the approach at the Italian pavilion has been ambitious at recent Biennales. Although the Italian pavilion usually favours complex installations, there seems to be such a sense of one-up-manship, that at times, it feels like the artist and curatorial team are biting off more than they can chew. This year, everyone had to line up under the sweltering sun to get into the Italian pavilion. That experience took me back to my youth in Melbourne, where I used to have to line up to get into bars and clubs. Every extra minute I waited, the anxiety and the dread grew, knowing I would soon be "assessed" by an agressive doorman or doorbitch who would decide if I was worthy enough to spend my money on drinks [back then, the drink of choice was vodka, but the music could range from dance/pop all the way through to heavy metal]. In any case, the strategy of single admission to the Italian pavilion is simply to limit the number of visitors in the space at any one time. It's an effective approach that makes sense with what's happening inside the walls of the show (and feels decidedly COVID friendly). I walked in hot, sweaty and grumpy and walked out feeling like Jodie Foster, wondering if the lambs have stopped screaming. If there are two pavilions at the Biennale that almost always leave me frustrated, its the Russian and Swiss pavilions.

There, I said it. This year, due to the invasion of Ukraine, Russia has essentially been "expelled" from the Biennale. I'll be honest. I'm not sure how I feel about the world's embargo on Russia when it comes to art, culture and artists. I’m going to be honest.

Almost every time I walk into the Belgium pavilion at the Venice Biennale, I walk away disappointed. But this year, I not only loved the exhibit, I actually made some extra time to return there, to ensure I ended my Biennale experience with a smile on my face. To say it’s been a tough couple of years for everyone would be an understatement. Despite the ongoing problems we’re facing with the combined challenges of a pandemic, war in Ukraine and the pressures we’re experiencing with supply chains and inflation in almost every corner of the globe, there are some lights on the horizon, if we actively search them out.

This year, after the pandemic scuttled the scheduled 2021 edition of the Venice Biennale, it’s finally back after three years and some false starts. I have to say, having lived out the pandemic in Italy, a country which was amongst the first and hardest hit, I had really been looking forward to returning to the Biennale. If you’ve visited this blog in the past, you may have noted that the Biennale is my favourite event in Italy, and one of the few times where I feel my masters in art curatorship gets a workout. |

Dave

|

|

|

Dave Di Vito is a writer, teacher and former curator.He's also the author of the Vinyl Tiger series and Replace The Sky.

For information about upcoming writing projects subscribe to the mailing list. Dave hates SPAM so he won't trouble you with any of his own. He promises. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed