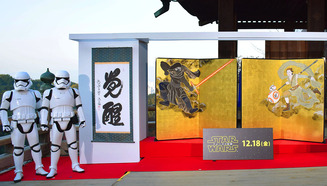

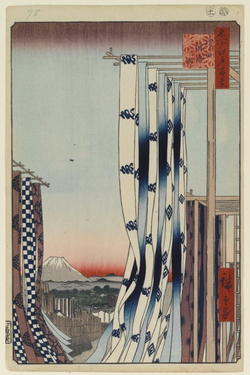

Au Mobile phone ad Au Mobile phone ad READERS of this blog will know that I am one of the enlightened few who knows that when it comes to just about everything, Japan is superior. Now, by everything, I mean everything related to popular culture. The force is awakening and we're going to be hopping mad about Star Wars all over again. Which means that you're going to see more and more Star Wars merchandise over the coming weeks. But let me remind you that if a novel idea exists, it exists in the Land of the Rising Sun. Because the Japanese are light years ahead of us when it comes to exploiting pop culture for all it's worth. And turning a pretty buck while they're at it. Here are just a handful of the smart and quirky ways that Star Wars iconography has been put to use in my mother land. Look at Vader playing nice in this old ad for the AU mobile service. Just wanna have a nice little snapchat with him!  Japantimes.co.jp Japantimes.co.jp I'm a complete nerd, and having studied Japanese art history, I love me a bit of rinpa or rimpa. There's something about a bit of gold leaf that just never goes out of style. In the past, artists produced large format screens so that they could show the force of Buddhist deities in a series of myths and legends. These days, artists like Taro Yamamoto are paying tribute, but using more contemporary figures like Jedis in the same settings. But only in Japan could you organise for a couple of storm troopers to stand guard while the screens are used to promote the upcoming film. If you ever go to Japan and are lost as to what to bring home as a present or souvenir, my philosophy is that you can't go wrong with a good noren. Noren are the lovely woven bolts of fabric that hang in Japanese doorways, whose designs are often symbolic of the seasons or events in the annual calendar. They're also used to signpost commercial businesses which is important in a place like Kyoto where electronic signage is often forbidden in the central, historic area.

Using the same screen printing philosophy, these amazing printed nassen, I think you'll agree, are a great mix of the Japanese aesthetic and certain iconic characters from the Star Wars canon. Nassen are like the relatives of noren. It's all about the unique textile and the dyes.

0 Comments

When I was at uni, I wrote a thesis on Japanese woodblock prints. You know, the kind that artists like Hokusai and Utamaro perfected and that gaijin like me just loved to bits while the Japanese just scratched their heads and wondered what all the Western fuss was about. Ukiyo-e which is the umbrella term for the woodblock genre is also a play on the Buddhist word which means the floating world. To simplify things for those not in the know, the floating world was kind of like an allegory for everything that is ephemeral and that often brings pleasure. It was from that Buddhist idea that the old pleasure quarters were often referred to as ukiyo - the floating world - because in places like Tokyo and Kyoto, where rigid social etiquette was already in place, the pleasure quarters were seen as a world of their own. These were places where courtesans, geisha and even kabuki actors were top of the pops. Places where everything had a price and where desires had no limits. Ukiyo-e (the prints) depicted all kinds of things. They were of artistic and graphic quality, but in a way they had a role in old Japan not unlike that of magazines and the print media today. They were seen as flotsam and although they are now collected and cherished, back then they were often like posters that you'd slap up on your walls to hide scuff masks. The first illustrated travel guides were ukiyo-e which spelled out the routes on the old Tokkaido highway with seasonal scenes designed in accompaniment. There are some amazing images of old Japan from those kinds of series, but the prints, which will large volume prints, also covered scenes of comedy, theatre and life in the pleasure quarters.  I think one of the things that attracted me to writing a thesis about the woodblock prints was that they often had humourous undertones to them. They often played on words (through their images) and they often left a pretty beautiful insight into Japanese thinking (especially during the Edo period). One of the other amazing things about ukiyo-e is that there seemed an endless scope of subject matter on offer. Much like magazines today. One of the most popular sub categories of the prints was shunga. The term represents the erotic side of our nature, and so shunga prints were all the rage for the way in which they explored desire and sexuality, often without boundaries. What you often get with shunga are scenes where genitalia are grossly exaggerated and where the figures are often indistinguishable across the prints. My interpretation of that was so that they could be used to kind of project your own identity onto the prints as you looked at them. I remember reading the definitive publication on shunga written by Timothy Screech and thinking, wow, this guy is brave and the Japanese, even from the 16th century were already peerless and ahead of us all. Well you know how I feel about Japan and how it really is the invincible, superior nation on earth. Except, I'm not so sure right now. You see, I stumbled across an article in which a modern day shunga volume has been published. And what it spells out- i.e that we have regressed to the point where we no longer have the maturity or humour to deal with something that is so innate to our being. Why? Because despite our advancements as people in some areas, we now live in a world where the idea of shunga needs to be censored by clown like emojis, basically stripping them of their value and importance, and robbing us of the opportunity to acknowledge and explore all of the facets of our personality without resorting to childlike, prudish self censoring. More at the Guardian on the truly offensive item like the one below. I ONCE wrote a thesis on Japanese woodblock prints. It was called The Shift to Intimacy. It was a thesis that looked at how those kooky woodblock prints were the first form of mainstream and wide scale publication, but that were also the first form of public/private art that the public really took to. I remember doing a solid year of research on the topic, reading everything I could find, and scouring museum collections near and far to help me illustrate my point. Back then, I worked under the supervision of two really ace Japanese art experts who tutored me and helped me get a grasp of what Japanese art is all about. In doing so, I recall being struck by how the Boston Fine Arts museum was basically a treasure trove of Japanese art: the best collection of Japanese works outside of Japan (as a result of the mass sale of Japanese art to Westerners during the second world war). For a period of time I was obsessed with ukiyo-e - the floating world - and the old, traditional pleasure quarters of historical Japanese life. Once you get into that headspace, it's very difficult to get out of it. I lived in Kyoto for a couple of years. Loved the place. Just obsessed with it, even now. I dug Tokyo as a place to visit, but Kyoto for me at least, was always the more interesting and layered place (and a hop skip and jump to Osaka, Kobe and Nara). Kids, the Kansai is where it's at. Kyoto is seen as the traditional home of culture in Japan. It was the country's capital for a really long time, and largely escaped the WWII bombings that otherwise flattened the cities in Japan. As a result it's a living, breathing city that is teeming with thousands of years of its history: from wooden palaces to ugly, brass decorated glass buildings from the seventies. It's a living map of culture. One of the things you can do in Kyoto is visit the Nishi-ji Textile Centre. Kyoto, being home to the traditions and culture of the country, is also seen as the home of the kimono. At Nishi-ji you can try on amazing kimono, like the one I snapped my dear friend in in the above photo. But it's the real deal there: you have to put on like seven or eight layers of the fabric and it weighs a tonne.  Monet, La Japonaise Monet, La Japonaise Dressing up in kimono or as a samurai, or even going the full scale and dressing as a geisha are among the kitschy things you can do in Kyoto and other parts of Japan. People have a fascination with that kind of stuff, and you can argue that playing dress ups in that context and that environment, regardless of your race or heritage, is a way of supporting the local economy and educating visitors by strengthening their ties to a foreign culture. Walk a mile in another man's shoes and all that. But there's been a big commotion in Boston in recent days at the Fine Art Museum. Among the objects in their collection is Monet's La Japonaise, which was a portrait of his wife Camille wearing a blonde wig and a kimono, surrounded by those other ubiquitous trademark items: paper fans. Let's just call it a period piece. It was a time when the European obsession with all things East was the norm and one of many contributions that made Japan, despite its distance, an enigmatic place on the map which seemed to scream culture and sophistication. Times have changed, and even on this blog I've noted how cultural appropriation is a huge controversy these days. While dressing up in traditional costumes or paying homage to cultural looks was still the norm even in the nineties, these days we are much more careful about things. Partly because we've revised the way East met West and because a lot of the way that we look at our differences is shaped by Western colonialism. That traditionally had a flow on effect with the exoticising or objectification of Asians (and of indigenous Australians, Africans, South Americans, Islanders etc. etc.). So what does that have to do with anything you ask my dears? Well, the Fine Art Museum attempted to tap into the current private/public fascination with art. You know, the one that finds its portal via social networks. Where people add a hashtag and tag themselves as being at blah blah blah place. The Boston Fine Art Museum attempted to take advantage of this by promoting Monet's piece and offering visitors the chance to dress up in a kimono (from their collections) and snap a photo of themselves (damn selfies!) alongside the work to be shared online. But not everyone is pleased, and in fact, the huge social outrage about this has led to the Fine Art Museum changing its approach. In the face of protests and people fuming online about yet more colonialism and objectification of cultures, the Museum has suspended the offer of dressing up but has instead ramped up the educational platform and its approach to getting visitors to engage with the kimonos in its collections. Is it an incorrect, imperialist context? Are we blowing things out of proportion, or is putting a kimono on in this way equal to black face? More at the NYT on this one, but I'd be curious to know your thoughts on the matter...let me know via the comments section.  It came as no surprise to see how prevalent video and film factored in the exhibitions on offer at the Biennale. The moving image is one of the most immediate forms of art, and as such, often makes a faster and more intimate connection with visitors than other formats. There is something about video that loosens people's inhibitions and natural barriers to art. The accessibility of the media offers artists the opportunity to connect with viewers without the need for a lot of supplementary material. I've both staged and visited exhibitions where people's confidence in reading art has only been assauged by a careful, studied look at any accompanying didactic informaton that sits beside or near the object. With video, people tend to be more confident in making their own decisions and judgements. Most people are well enough versed through television, music videos and film, to innately understand how to read images and look for clues when a narrative is on offer. What was interesting, if not a little surprising in Venice, was how warmly people tended to react to the video work. The scope of video was impressive. In the Japanese pavillion, Tabaimo's Teleco Soup was enthralling. A 360 degree immersive screen, made mostly of sloping walls and mirrors created an impressive and confined environment onto which Tabaimo's opera unfolded. A constant push pull dialectic offered viewers glimpses of the various elements of our world; an organic survey of the heavens, terra firma and all that lies beneath the earth's surface. Throughout the looped vision, we see the relaionship between man and his environment, or more specifically, the Japanese and their environment. The confines of the arching screens and the dark, enclosed pavillion seem to further support the idea of inversion and seclusion. The media release speaks of the sociological term Galapagos Syndrome, which was recently coined in Japan. Briefly, it makes the point that, as a society, Japan has increasingly seemed to turn inward in the face of globalisation. The insularity is a reflection of the self contained environment of the Galapogas. Of course, this insularity is nothing new; Japan was famously isolated (of its own choice) from the rest of the globe, and Tabaimo's addressing of this, along side her repeated use of environmental and natural motifs, makes for a modernised, if yet, still traditionally Japanese presentation of a modern (and not modern) idea. Pretty breathtaking. In accordance with the request of the Japanese pavillion, I have not uploaded any images of the Teleco-soup project. For more information, or visuals, visit the link posted on Tabaimo's name earlier. Jun Nakasuji, a Tokyo based photographer, visited the former Chernobyl nuclear plant in 2009 with the permission of the Ukrainian government, to document the current state of the landscape and surrounding abandoned cities.

His 2009 visit yielded a series of images which acted as a natural extension of his trademark images in which abandoned towns and structures are quietly documented as they stand in ghostly isolation, or occasionally, as they offer up the last of any resistance to the regeneration of nature around them. In the past these images have played not only with the beauty of desolation, but toyed with concepts surrounding production, construction and waste, differing from images of mere ruins from epochs of the past. His most recent visit, the second to the area in two years, seems more poignant after the environmental and potential medical devastation unleashed with the partial destruction of the Fukushima nuclear plant, which quite callously became the focus of people’s attention in the wake of the annihilation and lives lost in the fall out of the Sendai earthquake and tsunami. Loaded with an irrefutable symbolism of the unfolding catastrophe which has Japan and much of the world on edge, the choice to publish and exhibit images of a renewed visit to Chernobyl is an incredibly powerful one, especially in light of the jostling and increasingly political debate in progress which seeks to clarify at which level the current disaster at Fukushima should be classified. Images from Pripyat, once a half million strong town, within the thirty mile radius of the Chernobyl plant display the hallmarks of Nakasuji’s documentary style; cast in his favoured natural light, the spring time images take on Autumn like leanings, perhaps due to both environmental and photographic reasons, but there is no mistaking that the photographer is making it abundantly clear that here, in this unknown, anonymous town in the former Soviet Union, is the blueprint of what is to come for the area spanning the radius of the crippled Fukushima plant. That the accompanying text and interviews, which appear in his second book on Chernobyl, the about to be published ‘Cherunobuiri Haru‘ (Chernobyl in Spring), reinforce the perhaps not so widely known fact that the area of Chernobyl, remains, some 25 years on, still contaminated, and that the quest to contain the radiation and hazardous substances continues even today, delivers with such subtle force the kind of sledgehammer effect that organisations such as PETA or the various auspices of the United Nations can only dream of. The article at the Japan Times is a finely nuanced article which packs a hefty punch, all of course without histrionics and exaggeration. Nakasuji’s work and approach hold their own in a political minefield. |

Dave

|

|

|

Dave Di Vito is a writer, teacher and former curator.He's also the author of the Vinyl Tiger series and Replace The Sky.

For information about upcoming writing projects subscribe to the mailing list. Dave hates SPAM so he won't trouble you with any of his own. He promises. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed