|

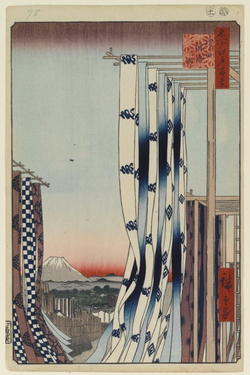

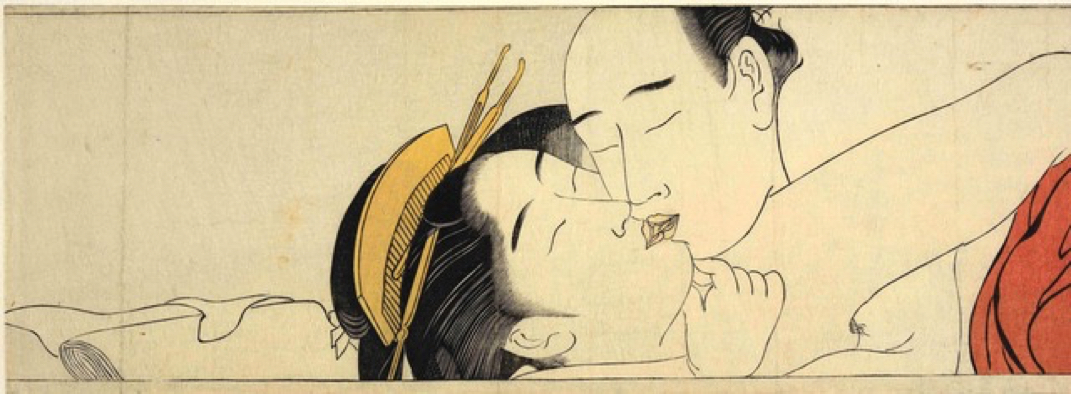

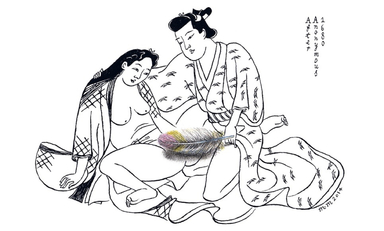

When I was at uni, I wrote a thesis on Japanese woodblock prints. You know, the kind that artists like Hokusai and Utamaro perfected and that gaijin like me just loved to bits while the Japanese just scratched their heads and wondered what all the Western fuss was about. Ukiyo-e which is the umbrella term for the woodblock genre is also a play on the Buddhist word which means the floating world. To simplify things for those not in the know, the floating world was kind of like an allegory for everything that is ephemeral and that often brings pleasure. It was from that Buddhist idea that the old pleasure quarters were often referred to as ukiyo - the floating world - because in places like Tokyo and Kyoto, where rigid social etiquette was already in place, the pleasure quarters were seen as a world of their own. These were places where courtesans, geisha and even kabuki actors were top of the pops. Places where everything had a price and where desires had no limits. Ukiyo-e (the prints) depicted all kinds of things. They were of artistic and graphic quality, but in a way they had a role in old Japan not unlike that of magazines and the print media today. They were seen as flotsam and although they are now collected and cherished, back then they were often like posters that you'd slap up on your walls to hide scuff masks. The first illustrated travel guides were ukiyo-e which spelled out the routes on the old Tokkaido highway with seasonal scenes designed in accompaniment. There are some amazing images of old Japan from those kinds of series, but the prints, which will large volume prints, also covered scenes of comedy, theatre and life in the pleasure quarters.  I think one of the things that attracted me to writing a thesis about the woodblock prints was that they often had humourous undertones to them. They often played on words (through their images) and they often left a pretty beautiful insight into Japanese thinking (especially during the Edo period). One of the other amazing things about ukiyo-e is that there seemed an endless scope of subject matter on offer. Much like magazines today. One of the most popular sub categories of the prints was shunga. The term represents the erotic side of our nature, and so shunga prints were all the rage for the way in which they explored desire and sexuality, often without boundaries. What you often get with shunga are scenes where genitalia are grossly exaggerated and where the figures are often indistinguishable across the prints. My interpretation of that was so that they could be used to kind of project your own identity onto the prints as you looked at them. I remember reading the definitive publication on shunga written by Timothy Screech and thinking, wow, this guy is brave and the Japanese, even from the 16th century were already peerless and ahead of us all. Well you know how I feel about Japan and how it really is the invincible, superior nation on earth. Except, I'm not so sure right now. You see, I stumbled across an article in which a modern day shunga volume has been published. And what it spells out- i.e that we have regressed to the point where we no longer have the maturity or humour to deal with something that is so innate to our being. Why? Because despite our advancements as people in some areas, we now live in a world where the idea of shunga needs to be censored by clown like emojis, basically stripping them of their value and importance, and robbing us of the opportunity to acknowledge and explore all of the facets of our personality without resorting to childlike, prudish self censoring. More at the Guardian on the truly offensive item like the one below.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Dave

|

|

|

Dave Di Vito is a writer, teacher and former curator.He's also the author of the Vinyl Tiger series and Replace The Sky.

For information about upcoming writing projects subscribe to the mailing list. Dave hates SPAM so he won't trouble you with any of his own. He promises. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed