|

I'm calling it c*ckgate.

Or should that be c*ckgrate. Lecce, where I currently reside, is famous throughout Italy. It's a Baroque jewel which with each passing year becomes a little more appreciated and loved by Italians and visitors. Its old town is a gleaming, cobbled town full of sandstone buildings that shimmy in the light here. It's a sophisticated Southern Italian town. But it has its own salacious past. For the most part, people from around here are considered to be laidback by most other Italians. But, there's been a lot of fuss here over the past few days. Why? Well, most of your guidebooks won't point it out: they're too busy pointing out the jewels of the city's crown: Il Duomo, Piazza S. Oronzo and the Santa Croce church. Refined and elegant examples of excellent workmanship and the mastering of the local limestone (pietra Leccese) if ever you'll see them. And those places along with the ampitheatres attract a lot of camera happy visitors. But there are other sites to behold in the city, that go beyond the religious history of the city. After all, it's become a city synonymous with aperitivos, live music and the booming university crowd that has added a much younger and playful dimension to the city. One place in particular offered up a window into the soul of the old town. If you stalked or crawled the city's back streets you may have been fortunate enough to stumble upon the most phallic window dressing that you'll see this far south from Amsterdam. In Via Palmieri one of the city's most unlikely icons has been sitting and attracting its own subcultural visitations. You see, the building on which the pleasure grate is positioned was purportedly once a pleasure quarters. A place of fun. Of...oh you know what I'm talking about. Well actually, no one is so sure of that, but it's the going theory. And at its peak, the house of fun commissioned a local blacksmith to create a protective window grate for the street facing window. And, to do the place justice, the craftsman created the wonderful phallic window grate that sat in front of the window, where it stayed, seemingly forever. It was a rare example of purpose built architecture and design dedicated to fun. Quite a departure from the more conventional religious expression which while wild, was always used to express religious ecstacy and not the joys of the flesh or other more playful aspects of life - but one that was immortalised in art and poetry. The window grate, like much of the city's other attractions, attracted its fair share of visitors who liked nothing more than to photograph it and move on, sometimes incredulous, sometimes simply ticking another thing of their lists. So what's the problem? The problem is that the building that the window sits on is now privately owned. And although the windows are reflective, the owners found it intrusive that their building was under 'constant' siege by camera wielding maniacs. Or something like that. So, they took it upon themselves to have the window grate replaced (during the night?) so that their privacy wouldn't be compromised any further. Enter huge social media shit storm. Leccese (if you're from Lecce you're Leccese) were up in arms over the owner's decision to remove a layer of the city's otherwise intangible history. And in subsequent days the city has been abuzz about city hall's reluctance to do anything about the removal of a prickly part of the city's history. Leccese, being Leccese, were up in arms and there's nothing like a bit of social media upheaval to get logical decisions made. Turns out that the heirs of the original owners had decided the grate was of dubious moral value and she didn't care much for the unwanted attention her window awning attracted. But the moral of the story? She's been instructed, by order of the city, to restore the original grate back to its original place. Because it's an important symbol of a vanished part of the city's history? No. Because she didn't have the necessary approvals or paperwork to remove it in the first place. Thank god for heritage protections. I'm gonna go snap me a shot of that grill as soon as it's back up (and as soon as I know the new owner's home and my popping camera flash can annoy the hell out of here.) Yay!

0 Comments

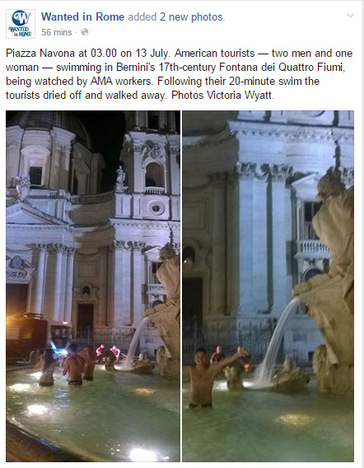

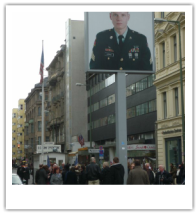

There are certain things that we all consider necessary in the big smoke. Transport, medicine, sanitation, utilities...these are the kinds of essential services that our cities tend to revolve around. Some get it right- and that's often a matter for Monocle or whoever to decide as to how well- and others have problems with even the basics. Having spent a really long time in Italy (and Rome in particular)I can tell you that some cities here get it right and that some...um...don't. Or can't. But if it's any consolation nobody seems to be happy about how things are run: those in service and those who use service are all often miserable. The most noticeable thing that goes wrong in a place like Rome is the transport. Let's face it. It's really shit. If you were to set your watch by the next due bus you'd be the new Marty McFly. Honestly, it's the worst public transport system I've seen in Europe, but whatevs. One of the annoying layers of transport in Rome is that you often have to factor in strikes on a Friday (or Monday). Because transport is legally deemed an essential service though, even on a strike day there has to be a minimum service on offer and a minimum notice period advising of the upcoming disruption. Rome's traffic is like those annoying accordions that you get held hostage to on the metro. It expands, gets noisier and becomes more unbearable on any day there's a strike when services are limited to the essential.That happens on days when things have been reduced to a bus an hour or, as often happens in Rome, morning and evening peak with a limited service and the rest of the day with virtually zilch. Why the long talk about the minimisation of services to their essential? Because in recent days a new law has been passed in Italy. One which now deems cultural sites- or rather, access to cultural sites- as being essential. Going on strike in a country like Italy where working conditions can be testing to say the least is something that happens in nearly every sector. Last week supermarket staff were on strike. But what made the news was a day a few months back when the staff at sites like Rome's Colosseum also went on strike, making the city's landmark symbol off limits to tourists. Workers in the arts and heritage sector here have it rough. There's very little money invested in sites and their upkeep, the average Joe works for a pittance and pay is often backpaid in many cases. But in going on strike, the cultural industry workers did something that not even the transport workers can. They literally robbed visitors of the opportunity to visit a site that many would have purposely made the trip to Rome for. And in doing so, at least in this version of the interpretation, they harmed Italy's international reputation more than the endless train, airport and sanitation service strikes ever could. The Italian government has decided that this is unacceptable. And as such, a very clear majority decided to pass a law that now renders cultural sites as part of the network of essential services in the country. This means that workers, regardless of how their issues may differ to those in the transport or other sectors, will now be required to file notice of their intention to strike, communicate that, and allow for some contingency which will allow the sites to remain open even on a strike day. Is it a good thing? Tourists may argue yes. Nothing like a certainty when you're doing the greatest hits tour. But for workers in a field where competition for roles is fierce, remuneration is poor and there's a murkier distinction between public and private operation, does singling that sector of the tourism industry out as being essential really count as being fair or lawful? Enshrining the erosion of their bargaining power into law seems a little heavy handed in my books. Particularly because for all the wealth tourism brings into a city like Rome, I would hazard a guess that most Romans wouldn't see access to those kinds of sites as being part of the essential services the city needs to offer- particularly if the end benefit goes to foreigners rather than the locals who, for better or worse, manage the sites.  AS I mentioned, when you live in Rome, despite the many grievances you might have with the way the city is run, there are very few things that unite all Romans. One of them is the abject stupidity and disrespect of visiting tourists who clearly get overwhelmed by the amazing city centre and treat it like a theme park or a water theme park in the summer months. You see, apparently, some people still think they are in a Fellini film when they visit Rome and that jumping into priceless, world heritage listed fountains is nothing to be ashamed of. Latest example of tourists gone wild? Wantedinrome reader posts photos of tourists swimming around in Bernini's recently restored Piazza Novana fountains. Expect a shit storm to (rightfully) explode. Seriously! Via Wantedinrome Facebook. I ONCE wrote a thesis on Japanese woodblock prints. It was called The Shift to Intimacy. It was a thesis that looked at how those kooky woodblock prints were the first form of mainstream and wide scale publication, but that were also the first form of public/private art that the public really took to. I remember doing a solid year of research on the topic, reading everything I could find, and scouring museum collections near and far to help me illustrate my point. Back then, I worked under the supervision of two really ace Japanese art experts who tutored me and helped me get a grasp of what Japanese art is all about. In doing so, I recall being struck by how the Boston Fine Arts museum was basically a treasure trove of Japanese art: the best collection of Japanese works outside of Japan (as a result of the mass sale of Japanese art to Westerners during the second world war). For a period of time I was obsessed with ukiyo-e - the floating world - and the old, traditional pleasure quarters of historical Japanese life. Once you get into that headspace, it's very difficult to get out of it. I lived in Kyoto for a couple of years. Loved the place. Just obsessed with it, even now. I dug Tokyo as a place to visit, but Kyoto for me at least, was always the more interesting and layered place (and a hop skip and jump to Osaka, Kobe and Nara). Kids, the Kansai is where it's at. Kyoto is seen as the traditional home of culture in Japan. It was the country's capital for a really long time, and largely escaped the WWII bombings that otherwise flattened the cities in Japan. As a result it's a living, breathing city that is teeming with thousands of years of its history: from wooden palaces to ugly, brass decorated glass buildings from the seventies. It's a living map of culture. One of the things you can do in Kyoto is visit the Nishi-ji Textile Centre. Kyoto, being home to the traditions and culture of the country, is also seen as the home of the kimono. At Nishi-ji you can try on amazing kimono, like the one I snapped my dear friend in in the above photo. But it's the real deal there: you have to put on like seven or eight layers of the fabric and it weighs a tonne.  Monet, La Japonaise Monet, La Japonaise Dressing up in kimono or as a samurai, or even going the full scale and dressing as a geisha are among the kitschy things you can do in Kyoto and other parts of Japan. People have a fascination with that kind of stuff, and you can argue that playing dress ups in that context and that environment, regardless of your race or heritage, is a way of supporting the local economy and educating visitors by strengthening their ties to a foreign culture. Walk a mile in another man's shoes and all that. But there's been a big commotion in Boston in recent days at the Fine Art Museum. Among the objects in their collection is Monet's La Japonaise, which was a portrait of his wife Camille wearing a blonde wig and a kimono, surrounded by those other ubiquitous trademark items: paper fans. Let's just call it a period piece. It was a time when the European obsession with all things East was the norm and one of many contributions that made Japan, despite its distance, an enigmatic place on the map which seemed to scream culture and sophistication. Times have changed, and even on this blog I've noted how cultural appropriation is a huge controversy these days. While dressing up in traditional costumes or paying homage to cultural looks was still the norm even in the nineties, these days we are much more careful about things. Partly because we've revised the way East met West and because a lot of the way that we look at our differences is shaped by Western colonialism. That traditionally had a flow on effect with the exoticising or objectification of Asians (and of indigenous Australians, Africans, South Americans, Islanders etc. etc.). So what does that have to do with anything you ask my dears? Well, the Fine Art Museum attempted to tap into the current private/public fascination with art. You know, the one that finds its portal via social networks. Where people add a hashtag and tag themselves as being at blah blah blah place. The Boston Fine Art Museum attempted to take advantage of this by promoting Monet's piece and offering visitors the chance to dress up in a kimono (from their collections) and snap a photo of themselves (damn selfies!) alongside the work to be shared online. But not everyone is pleased, and in fact, the huge social outrage about this has led to the Fine Art Museum changing its approach. In the face of protests and people fuming online about yet more colonialism and objectification of cultures, the Museum has suspended the offer of dressing up but has instead ramped up the educational platform and its approach to getting visitors to engage with the kimonos in its collections. Is it an incorrect, imperialist context? Are we blowing things out of proportion, or is putting a kimono on in this way equal to black face? More at the NYT on this one, but I'd be curious to know your thoughts on the matter...let me know via the comments section.  Source: http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cretto_di_Burri Source: http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cretto_di_Burri This is Cretto di Burri, an amazing piece of land art created by Alberto Burri in Sicily from 1984-1989. But more on that later. I'm thinking about the people of who find a way of being art warriors. People who do something to protect our heritage and make our environments something that we can continue to love and to appreciate. I kind of dig these guys. But if you don't understand Italian I'm going to simplify it all for you. They're the Legambiente, which translates to the Environmental League in Italian. Think of them as a greens group, who, in addition to addressing the toll of human activity on the Italian environment also take a comprehensive look at cultural heritage in Italy, with the view that the patrimony or cultural heritage is multi layered and exists in town and country.. They came to my attention after coining the term archeomafia. The concept was based on the black market for stolen artifacts and products looted from the innumerable archaeological sites in Italy, as well as misconduct in cultural institutions which placed objects at risk. Each year they tabled a report to determine the cost of illegal environmental and cultural activity to the environment, and to the state as a whole. Because some people only react to cold hard numbers these days. From the 27 May thru June 2nd, they are spearheading a nationwide event called Voler Bene all'Italia which translates to something like Love (your) Italy. The event, with a major focus on Naples, one of Italy's most underrated and challenged cities, will feature almost 200 events in various parts of the country designed to get citizens to better appreciate their heritage with the end goal of encouraging citizens to be more mindful of their environment(s) and to do their bit in protecting them. In Naples, a city whose current state belies the fact that it was once one of the richest and most important cities in all of Europe, participants in the event will be encouraged to reexamine their environment. Naples was, even further back, the mother city: Neapolis, and any visit there will peel thousands of years of continuous settlement before your eyes. It will blow your mind if you can get over the fear of the criminal element that it is now associated with. Italy's rich heritage means that many of its most notable sites are known the world over. Sites that belong not only to the Italians, but to the world in general. Problems with the economy and funding have meant that many of these sites have fallen into disrepair. In some cases, EU intervention has been widely documented and helped turn back the scope of degradation. But part of the problem, in any country facing economic difficulty, is raising the awareness of how cultural heritage needs defending, even in the most difficult of fiscal times. This is a country where even some of its smallest towns play host to historical sites of incredible beauty and relevance, and whose tourist based economy would flounder should they no longer be in a condition to attract visitors. So, if you're in Italy between the 27th of May and the 2nd of June, click on the link, get your Google translate button at the ready, and discover something off the beaten track. If you're near Trapani in Sicily, perhaps you might want to head out to Cretto di Burri, whose restoration is going to be announced as part of the week long festivities. You'll be doing your part, and it could do you some good to get away from the busloads of tourists whose greatest hits tours miss the essence of this country's spectacular and varied history.  I AM not a huge fan of MAXXI in Rome. Aside from being a means through which the Northern parts of the city can be better utilized to capitalize on the Art Academy quarter of the city, and playing its part in re-asserting the presence of contemporary art in a classical city like Rome, MAXXI leaves me cold. When the Zaha Hadid designed building finally opened in 2010, it already felt stale to me. No coincidence that years of delays and other issues saw to the project taking almost ten years to be realised, by which stage the revolutionary building design seemed to scream; you've seen me before in a million other capital cities. The art at MAXXI feels more modern than contemporary, and this is an important thing to understand in Italy, because modern art in Italy envelopes the last few hundred years, whereas contemporary art is that which is produced in the now. Invariably, when you visit MAXXI, you get a mixed idea of what modernity means. You're as likely to encounter artwork from the seminal 1960s and 1970s, when Italian artists were at the forefront of the contemporary and avantguard scenes, as artwork from more recent years, in which the collections place emphasis on international artists, partly because Italian artists haven't connected with their public in recent years to the same scale as international artists, because they haven't been able to maintain the urgency, that cutting edge ability that seemed to come so naturally in the mid twentieth century. This is a direct result of the destruction of arts education and training in this country, a brain drain which has weakened innovation in the arts here in the same way that it has weakened Italy in technology, science and pretty much any other smart industry. MAXXI was envisaged as being the centre of Italy's contemporary arts scene, and as such, was part of a huge push to rebrand Rome as a pivotal European centre for contemporary art, a huge undertaking, given the identity clash between old and new that is constantly played out in Rome. But MAXXI, in just its second year, is already facing other big challenges. Recently spotlighted in the news due to funding issues, the museum finds itself in the unenviable position of being a big new player that already has an uncertain future. Coupled with the appointment of an administrator, talk currently suggests that the government, in its current austerity drive, has drawn the line and plans to cut funding, emphasizing the point that its initial funding was provided under the condition that MAXXI sought out private partners to sustain it on an ongoing basis. This brief Italian article suggests that MAXXI has so far failed to do so, and that in not doing so, risks not being able to pay staff wages beyond another few months, let alone continue to stage exhibitions and events that it so desperately needs to in its attempt to define its place in the contemporary European scene. MAXXI of course is not alone in this dire situation. In recent weeks, by museology standards, events have turned almost apocalyptic. Click Read More to continue this post.  I PERSONALLY have some very good memories from Checkpoint Charlie. I remember when I first went to Berlin in the summer of 1996 and first fell in love with that city, Checkpoint Charlie had some kind of effect on me. Not in the same way or with the same gravity that seeing the wall or Alexanderplatz did, nor was it even comparable with being reuinted with my friends who lived there who I hadn't seen for over a year. CC offered something intangible. Back in 1996 the streets around the area were already aligned with makeshift carpets, covered with pins and badges bearing old Communist designs, but the surrounding streets were oddly deserted in contrast. The museum which was already in place there felt like a sobre reminder about how the world got things so wrong back in the thirties and forties, and although it had the authenticity of the Hard Rock Cafe, it had a spirit and purpose which couldn't be faulted, and a gift shop that made perfectly light of war paraphenalia and imagery. Berlin is no longer just the whacky, cool city that inspired me back in the 1990s, a burgeoning place of beer gardens and awkward conversations and a Northern German mentality. It has become one of the premier cities of Europe again, where aside from the architecture, it gets harder and harder each day to distinguish the differences between Old East and Old West. The film Goodbye Lenin! is as good a summation of the new versus old mentality if you want to look into that further, but sometimes history and culture are intangible, especially when the representat structures have been razed or destroyed. Even when things are based on replicas or rebuilds, they can still be authentic homages to or reminders to another time, another event, another history, assuming that the surrounding area adds that otherwise missing authenticity. So it was with complete dismay that I read this article about even more changes that seemed to have been made to the area around CC. Where is it that we, as people, as cities, as governments draw the line between rampant commercialism and maintaining at least a semblance of dignity?  I'M USUALLY quite forgiving of people who are patriotic or nationalistic. It amuses me, but I know that I am probably just as guilty, especially in those more trying moments of life in a foreign country. We take comfort in thinking that we are part of a greater group of achievers and achievements. There is of course an ugly side to patriotism. Its the blind rabbidism that is based on half truths, assumptions and plain rubbish and I unfortunately encounter it here on a regular basis. An example here in Italy is of how Italians perceive their country. True, recent decades haven't been very kind to Italy. They have been caught up in a vicious cycle of politics, stagnation and economic woes and now, with a technocratic government in place are paying the price by means of an endless stream of new taxes and an annhilation of worker's rights in an attempt to modernise the economy. So, when Italians tell me that Italy is home to more than 70% (90% on occassion) of the world's patromonio, that is, cultural heritage, I bite my tongue and let them continue believing it. I mean, everybody is at them and on their case about everything that it seems really petty for me to correct them. What they are referring to infact is the UNESCO World Heritage listing. But maths is probably not a strong point in this country. It is true that Italy has more sites on the respective lists than any other country, and that like any other person who dabbles in a bit of nationalism, they deserve to be proud of their heritage, but, its not the one horse race some Italians would have you believe. Italy, by the latest count, has 44 sites listed for their cultural significance. That's six more than Spain (38) and eleven more than both Germany and France's total of 33. Overall, on the combined list of natural and cultural sites, Italy comes in trumps again with 47, with Spain close behind with 43 and China with 41. These are impressive numbers. There is an entirely other debate to be had about the UNESCO listings, but its important to also consider that there are approxiamately 725 sites around the world that have qualified for status. Italians who cling to this idea that their cultural heritage is the centre of the universe probably could do with a cup of tea and a few deep breaths before being made aware of this. Click on READ MORE to continue the post.  On the weekend I made a return trip to Tivoli, which, these days, has almost become part of the conurbation of Rome. It's a relatively easy place to reach being just 30km or so away from Rome, and as such, is home to many of Rome's foreign workers given the proximity to the city and its lower cost of living in comparison to Rome's. If you make it past the sulphuric quarries at the city's entry, you'll quickly realise that Tivoli is also home to two UNESCO World Heritage sites, the Villa Adriana (pictured) and Villa d'Este. With 47 listings, Italy is the most represented country on the UNESCO listing, which should stand as a reminder that there are copius amounts of culturally significant sites to visit in Italy with or without UNESCO status. Culture is big business in Italy; the culture sector accounts for around 12% of the entire economy, but with Italy's stalled economy, there is never enough money to manage the upkeep of Italy's many monuments and cultural sites. Increasingly, Italy is catching up with other nations and seeking corporate support in the management and upkeep of its heritage. Newsweek spelled out their own figures, pointing out that heritage sites are not just struggling to stay afloat, but that they are literally crumbling. In January 2011, Tods made headlines with their agreement to fund restoration works of Rome's Colosseum and Milan's La Scala theatre, and in recent days talk has been circulating that Diesel plan to fund the restoration of Venice's Rialto Bridge. Which brings us to the case of Tivoli. Although the town and its villas are significant, and indeed, quite spectacular, increasingly dwindling visitor numbers attest to the competition in this country for the visitor's dollar. Tivoli's two villas, one located at the foot of the town, and the other, Villa D'este, in its centre, are operated seperately. A entry ticket during the summer forVilla d'Este is currently 11 euro, whilst a similar price is also asked at Villa Adriana. The latter, an outdoor site which is currently one of many throughout Italy which is not in full operation (areas are cordoned off due to their unsafety), has seen its ongoing requests for maintenance funding only being partially granted by the Ministry of Culture. A recent article suggested that Villa Adriana in particular, despite its grave needs for restoration works, is not considered a priority site, particularly in the face of an increasingly shrinking national culture budget. The question then, is it the responsibility of a site of international significance (as recognised by UNESCO) to find alternate forms of funding from the private sector. Or, could a joint ticket scheme between the villas improve patronage and boost their spending pots? |

Dave

|

|

|

Dave Di Vito is a writer, teacher and former curator.He's also the author of the Vinyl Tiger series and Replace The Sky.

For information about upcoming writing projects subscribe to the mailing list. Dave hates SPAM so he won't trouble you with any of his own. He promises. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed